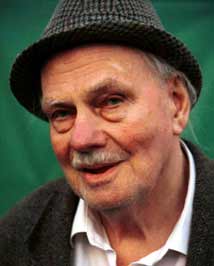

| [From The Living Tradition] To most people in the Scottish folk-scene the name Hamish alone is sufficient to identify him. The ability to refer to somebody by his first name alone is a true mark of recognition. Hamish Henderson is a big man in many ways. His contribution to the folk revival is huge. His work at The School of Scottish Studies, his work with collectors like Alan Lomax and his involvement with The People's Festival Ceilidhs of 1951, 52 and 53, which were in many ways the predecessors of the Edinburgh Fringe Festival, had an impact throughout Britain. A whole generation of young singers and musicians were exposed to a living tradition of folksong and classic ballads as the ceilidhs introduced performers such as Jessie Murray, Jeannie Robertson, Jimmy MacBeath, John Strachan, Flora McNeil and The Stewarts of Blair. Although the events were relatively small in terms of audience number, their influence on the folksong revival was immense. Hamish has called them "epoch-making". |

The People's Festival Ceilidhs were important not only for Scotland but for several other countries as well. Scotland was lucky in having so many outstanding traditional singers and musicians, and visitors from Italy in 1951 and 1952, were influenced by these ceilidhs and imported the ideas to Communist Party events in Italy such as the Feste dell'Unita.

Hamish has referred to himself, and many of the poets whom he knew, as having "grown up for war". Born on November 11th, 1919, exactly a year after the armistice that marked the end of the First World War, he was nineteen when war was declared in 1939. Hamish worked in military intelligence; he served with the 51st Highland Division, was in North Africa, and later worked with the Partisans in Italy. By the time of the Battle of El Alamein he was still only twenty-two. This battle was one of the major formative events of his life and he still feels very close to it.

Before the war started, Hamish was politically very much to the left and what happened in the war helped to solidify his political beliefs. The citizen army which gradually built up in the Middle East to face Rommel was a literate army, its soldiers the beneficiaries of the 1918 Education Act, which differed greatly from the set-up a quarter of a century earlier. In the First World War the voice of the ordinary swaddy was the soldier's folk-song and although the Second World War also produced a lot of folk-song, the striking new thing was the amazing flowering of written poetry. Hamish has written much about this and in a section of his book "Alias MacAlias", he closes with a poem by Douglas Street called "Love Letters from the Dead" and subtitled "A commando intelligence briefing".

"Go through the pockets of the enemy wounded Go through the pockets of the enemy dead - There's a lot of good stuff to be found there - That's of course if you have time", I said "Love letters are especially useful, It's amazing what couples let slip - Effects of our bombs for example. The size and type of a ship. These'll all give us bits of the jigsaw. Any question?" I asked as per rule-book;

A close-cropped sergeant from Glasgow, With an obstinate jut to his jaw, Got up, and at me he pointed: Then very slowly he said: "Do you think it is right, well I don't, For any bloody stranger to snitch What's special and sacred and secret, Love letters of the dead?"

During the war Hamish worked with several Scots regiments. He could sense that people were frustrated as there in the field of battle, these regiments had a very definite sense of identity, but when they came out of the army that dissolved. Now all that has changed and people increasingly feel that they should resume their Scottish identity - rightly so in Hamish's opinion - and he is looking forward to the next step with the re-establishment of a Scottish Parliament. "People now increasingly realise what a fantastic nation we were and are. The amount of concrete benefit that Scots gave to the human race in the eighteenth century is astonishing, not only in the field of philosophy but in discoveries and so on. Many things are coming out in the open now that weren't realised even ten to fifteen years ago".

Hamish is proud of being a Scot but never in a narrow nationalistic sense. With him, national pride and an international outlook go hand in hand. "I am definitely proud of being Scots - and incoming people with similar ideas are quite entitled to express it as well".

Before the war, Hamish studied at Cambridge University and whilst he was there spent a lot of time working on folk-song collections, in particular that of Gavin Greig. He realised that there was a lot of work still to do, a realisation that was to lead on to his work after the war. When he came out of the army Hamish looked to interest himself and to give any service that he could to folklore studies. He had to earn a living but wanted to do that whilst working on folksong and an involvement with the politics of the left.

His book of war poetry "Elegies for the Dead in Cyrenaica" won him the Somerset Maughan award - a travelling scholarship. He secretly thought that this was an attempt to get him out of the country! He decided to go to Italy and to work on translating the works of Gramsci - a philosopher of the left - but he didn't finish that work in Italy because he was thrown out! Hamish had been in contact with many left wing people when he was there - people who nowadays would be regarded as 100% OK but this was during the Cold War period. He was regarded as "a danger to Italy" and was ordered to leave. He ended up back in Cambridge and continued his work on the translations in the University library.

Having finished this work Hamish needed to earn a living and got a job at Queens University Belfast, always a great centre for folklore studies, and later became one of the pillars of the School of Scottish Studies. The idea of a "School of Scottish Studies" within The University of Edinburgh had been around for some time but had never been established. Hamish had met the boss of the Department of Anthropology of the University when he was in Egypt - a man called Abercromby - and he invited Hamish to his house where he played him some recordings of traditional songs and proceeded to tell him about them. Abercromby was not aware of Hamish's interest and knowledge of folksong and Hamish found himself correcting some of Abercromby's statements about the songs. He later invited Hamish to another party and introduced him to Professor Newman, the professor of music. They were in the process of being interested in the creation of a School of Scottish Studies and these contacts led Hamish to being one of the first people to work for the School.

Very little collecting was being done in Scotland at that time. Alan Lomax was working in America on "folk and primitive music" and wanted to come over to Scotland to collect. The Americans had no knowledge of Gaelic and needed help with that. Hamish was asked to "help these incoming Yanks" and did so enthusiastically. One important thing for Hamish was that the Americans had recording equipment! There was no sound in Gavin Greig's notebooks and this was a great opportunity to let people hear what the songs sounded like. On their first collecting trip they expected to come back with about half a dozen songs but came back with a huge amount of recordings. (All these recordings still exist in the School).

Hamish enjoyed himself during this period. Before the School had rooms of its own there was a room (now the staff club) which wasn't being used much and it was commandeered for singing, music and ceilidhs. Later on the School moved to George Square where it still is today. Hamish has officially retired from the School but still has his room there!

Hamish has contributed several fine songs to the tradition including "The Freedom Come All Ye" which has been put forward quite credibly as a candidate for a National Anthem. Many Scots would have difficulty in understanding the words, yet the song was and is sung - in Scots - all over the world. It is clear that the sentiment was easily understood. Hamish never liked the idea of the song being seen as a National Anthem - in his view it isn't a national anthem - but if people want it as an anthem then his view is "let them take it". Hamish rather thinks that it could be an International Anthem and in many ways it has been that.

It was taken up in France in the early 60s, in China and in Italy where Hamish sang it at a party held by the son of one of the Presidents of Italy where he was able to link it to Italian songs such as Bandiera Rosa. Poetry has to be understood as poetry and translations usually fall well short of the original. Although the song didn't translate easily, there were many Italian songs at the time that echoed its ideas. My own experience of hearing Hamish singing it was at one of Ray Fisher's late night ceilidhs at Newcastleton Festival. On that occasion Hamish brought the song totally to life and I have no problem understanding how an Italian or French person could gain an immediate understanding of the song.

The idea of writing a song to the first world war tune, "The Bloody Fields of Flanders", came to Hamish after he had been up to the North East of Scotland seeing Ken Goldstein, an American who was attached to The School of Scottish Studies. Ken had been lodged up in the Northeast and Hamish made regular trips up to see how he was getting on. The night before, he had been singing some tunes to Ken who had expressed a liking for that tune so Hamish said that he might write a song to it. The next day Hamish was travelling back by train from the Northeast to Aberdeen and then to Edinburgh. It was a blustery day as he travelled down the coast - which explains the references to the bay in the first verse - and by the time he got back to Edinburgh the song was more or less complete.

Roch the wind in the clear days dawin' Blows the cloods heelster gowdy ow'r the bay But there's mair nor a roch wind blawin' Through the great glen o' the warld the day. It's a thocht that will gar oor rottans A' they rogues that gang gallus fresh and gay Tak the road an' seek ither loanins For their ill ploys tae sport an' play

The first few lines are easy, anybody can understand the raw winds blowing the clouds head over heels. "But there's mair nor a roch wind blawin' through the great glen o' the warld the day" refers to the fact that at that time there were great thoughts and ideas, including some quite turbulent ones, on the go in Scotland and throughout the world. Hamish translated the image of "The Great Glen" as he travelled south from a local to a global reference. The later part of the verse is simply saying that "if there were people who were against these ideas then they weren't going to get away with it much longer. They could bugger off so to speak!"

Nae mair will the bonnie callants Mairch tae war when oor braggarts crousely craw, Nor wee weans frae pit-heid an' clachan Mourn the ships sailing doon the Broomielaw. Broken families in lands we've herriet Will curse Scotland the Brave nae mair, nae mair. Black and white, ane til ither mairriet Mak' the vile barracks o' their masters bare.

Hamish didn't like the idea of anybody going out to War again. "There are plenty of good things, many efforts in Scotland, which can be excluded from this bloody military business. Not that I should say too much about that because I was in the war for quite a long time, but if you have got to do that - you may as well better do it. But the idea of equating Scotland with a military set-up, which is done by so many people, - that I felt should somehow be rejected so I found a place for its rejection in the song."

So come all ye at hame wi' freedom Never heed whit the hoodies croak for doom In your hoose a' the bairns o' Adam Can find breid, barley bree an' painted room. When MacLean meets wi's freens in Springburn A' the roses an' geans will turn tae bloom And a black boy frae yont Nyanga Dings the fell gallows o' the burghers doon.

"I spent quite a lot of time on the last verse. We had been talking about John MacLean the night before. He had heard my song "The John MacLean March" but he didn't know much about John MaLean. I said that I thought that some of the ideals needed to be resuscitated."

It is a very optimistic song. "I felt that things were about to happen and they have happened. It's a very different Scotland now from what it was in 1947."

Acknowledgements

The story of the School and Hamish's contribution to it and the folk revival are outside the scope of this article. The quotations here are taken from an interview with Hamish in February 1999 and some background information was taken from his book Alias MacAlias - "Writings on Songs, Folk and Literature" by Hamish Henderson, Published by Polygon. The words to The Freedom Come All Ye were printed with the permission of Hamish.

JEAN REDPATH

| Blessed with a sweet, but slightly roughened mezzo-soprano as gentle as mist and haunting as the highlands, Jean Redpath is one of the definitive interpreters of Scottish traditional songs. She is also a noted folk music ethnographer who has played an important role in the reconstruction of nearly forgotten Scottish songs and has been a lecturer at Scotland's Stirling University since 1979, and has also lectured regularly at Weslyan University, CT, and other prominent institutions including Harvard. She was born in Fife country outside Edinburgh. Her father played hammered dulcimer and her mother was well versed in Scottish oral history, most of which was passed from mother to daughter via songs. |

One of four daughters, their mother passed on the music to each. Her knowledge of the ancient songs proved useful while Redpath was attending the School of Scottish Studies at the University of Edinburgh and had begun formal research into her native ballads and compositions. She emigrated to New York in 1961 where she began singing in Greenwich village coffeehouses. Redpath also gave formal concerts at events such as the Lincoln Center's Mostly Mozart Festival and soon became an extremely popular performer on the folk circuit. Not only did they love her unique, sensitive voice, audiences were also impressed by her knowledge about the over 400 songs in her repertoire and the fascinating insights about the music that Redpath offered during her concerts. In 1963, she sang for the first time at the new School of Social Research and this led her to sign with Elektra where she recorded through 1975, when she switched to the Vermont-based Philo label. With them she has become one of folk music's most prolific recording artists. One of her most notable achievements has been an ongoing project to record all of the songs written by Scotland's poet laureate Robert Burns. Out of 22 planned volumes, only seven were completed due to the death of producer Serge Hovey. Other well-known Redpath series include a compilation of Scottish songs written by women, including Lady Nairne (1986).

In addition to recording and performing live, Redpath has also appeared on such radio programs as "Morning Pro Musica" on Boston's WGBH public radio station. Between 1974 and 1987 Redpath was also a regular on Garrison Keillor's Prairie Home Companion radio show. ~ Sandra Brennan, Rovi